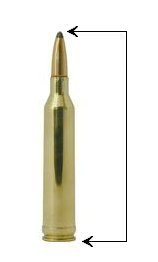

Over-All Length (OAL)

- explained in detail -

I'm always finding shooters looking for a more complete understanding

of the term "over-all length" (OAL) and how to find the best

length for their handloads. Most reloaders have noticed that

reloading manuals show one specific OAL for every different caliber.

This OAL dimension shows the industry standard (SAAMI spec.) for

a particular cartridge. Those published loads have been tested

to be safe at that specific length, and they will always fit in your

magazine. However, finding the "optimum" OAL for your particular

rifle requires a bit more information than most reloading manuals

provide. That's where the confusion sets in.

Understanding the unique bullet ogive (side of each bullet) will help

clear things up. The bullet ogive is much more relevant than the

actual OAL regarding chamber pressure. This article explains

"the rest of the story".

Factory ammo is also made according to industry standard

dimensions so your handloads will fit in any rifle of the same caliber,

and their ammo will always fit in your magazine. As a result,

they seat their bullets at least .100" deeper than necessary. Some rifles

(especially Weatherby Magnums) have well over .250"

of free-bore (distance to the rifling). They do this to safely

reach the highest velocity possible. On most production rifles,

if you seat your bullets close to the rifling, your handloads will be

too long to fit in your magazine. Finding the optimum OAL for

maximum accuracy usually requires you to reduce the distance that the

bullet travels before it contacts the rifling. This also helps

maintain concentric alignment between bullet and the bore, so that your

bullet gets a good start down the barrel.

Setting the OAL correctly for your "particular"

chamber is the cheapest accuracy improvement there is. However,

increasing the OAL will increase chamber pressure. To understand

why chamber pressure is increased, think about this example of "forward

momentum". A car can easily drive over a curb with a little

running start; but if you park right up against the curb and step on

the gas - it requires a whole lot

more force to start moving. Keeping this in mind, it's easy to

understand why seating your bullet against the rifling increases

chamber pressure. When we increase the OAL, we need to work up

loads with caution, and expect chamber pressure to increase.

Experienced shooters know that this is one essential step to improve

rifle accuracy. The optimum length of accurate handloads will

almost always be quite a bit longer than factory loads.

We need to remember that the tip of the bullet is

not what contacts the barrel. Actual contact with the rifling

occurs along the side of the bullet, so that's where the OAL

measurement should be made. The picture at the right shows a

"slotted case tool" that I made to determine the exact OAL measurement.

This length measurement is based on where the bullet contacts

the rifling. I have one of these modified cases for each rifle

caliber that I reload. Just take a resized case, and cut 3 or 4

slots in the neck. This is an easy project with a Dremel tool

using a cut-off disk. This makes a great chamber length gauge

that will grip a bullet with just enough tension to hold it in place.

This becomes an OAL gauge for one specific caliber using one

particular type of bullet.

We need to remember that the tip of the bullet is

not what contacts the barrel. Actual contact with the rifling

occurs along the side of the bullet, so that's where the OAL

measurement should be made. The picture at the right shows a

"slotted case tool" that I made to determine the exact OAL measurement.

This length measurement is based on where the bullet contacts

the rifling. I have one of these modified cases for each rifle

caliber that I reload. Just take a resized case, and cut 3 or 4

slots in the neck. This is an easy project with a Dremel tool

using a cut-off disk. This makes a great chamber length gauge

that will grip a bullet with just enough tension to hold it in place.

This becomes an OAL gauge for one specific caliber using one

particular type of bullet.

I use this "split case tool" to do find the exact

distance between the bullet and the rifling. With the test

bullet seated in my "split case tool", simply insert this round into

your chamber. The rifling will push the bullet deeper into the

case. Then carefully extract the round without disturbing the

bullet. After this gizmo is extracted, you can measure it from

the bullet ogive back to the base of the cartridge. This

measurement is then used to adjust the seating depth of your dies and

comparing to that measurement to your completed handloads.

The picture at the left shows another use for our Digital Headspace Gauge.

It is shown measuring the "split case tool". At this

point, just zero the gauge and then measure your handloads. This

gauge will then display the distance to the rifling that YOUR handloads

will have in YOUR particular rifle. In most cases a -.002"

jump to the rifling is ideal. Due to the irregular point on most

bullets, you can't expect to measure a consistent OAL to the tip of the

bullets. Except for a good fit in your magazine, the total

over-all length is not as important. It is more accurate to

measure the over-all length of your cartridges from the bullet ogive.

The picture at the left shows another use for our Digital Headspace Gauge.

It is shown measuring the "split case tool". At this

point, just zero the gauge and then measure your handloads. This

gauge will then display the distance to the rifling that YOUR handloads

will have in YOUR particular rifle. In most cases a -.002"

jump to the rifling is ideal. Due to the irregular point on most

bullets, you can't expect to measure a consistent OAL to the tip of the

bullets. Except for a good fit in your magazine, the total

over-all length is not as important. It is more accurate to

measure the over-all length of your cartridges from the bullet ogive.

Your barrel will eventually develop enough throat

erosion to increase the OAL setting for your rifle. Magnum

calibers (and several other hot cartridges) usually cause considerable

throat erosion after firing just a few rounds in a new barrel.

However, that wear will slow down considerably after the barrel is

broken in. When testing the accuracy of handloads for hunting

rifles, start experimenting with the longest OAL that will fit in your

magazine. Then start making your handloads in .003" shorter increments until you find the OAL that shoots best. I usually settle on the longest OAL setting

that will shoot well, and fit in the magazine.

If you are seeking the ultimate accuracy (and if you don't plan to use your magazine) you should start at least .001" behind

the rifling, and try reducing the OAL in .003"

increments, until you come up with the most accurate load. I

always avoid seating the bullet long enough to contact the rifling,

because you will eventually need to extract a loaded round. When

that happens, you could find that you have a bullet stuck in the

rifling. You'll become aware of this as your case pulls away

from the bullet, spilling powder all over the place.

Maximum accuracy is only possible after you've

found the optimum OAL for your particular chamber. Give this

method a try, and see how much your accuracy improves.